-40%

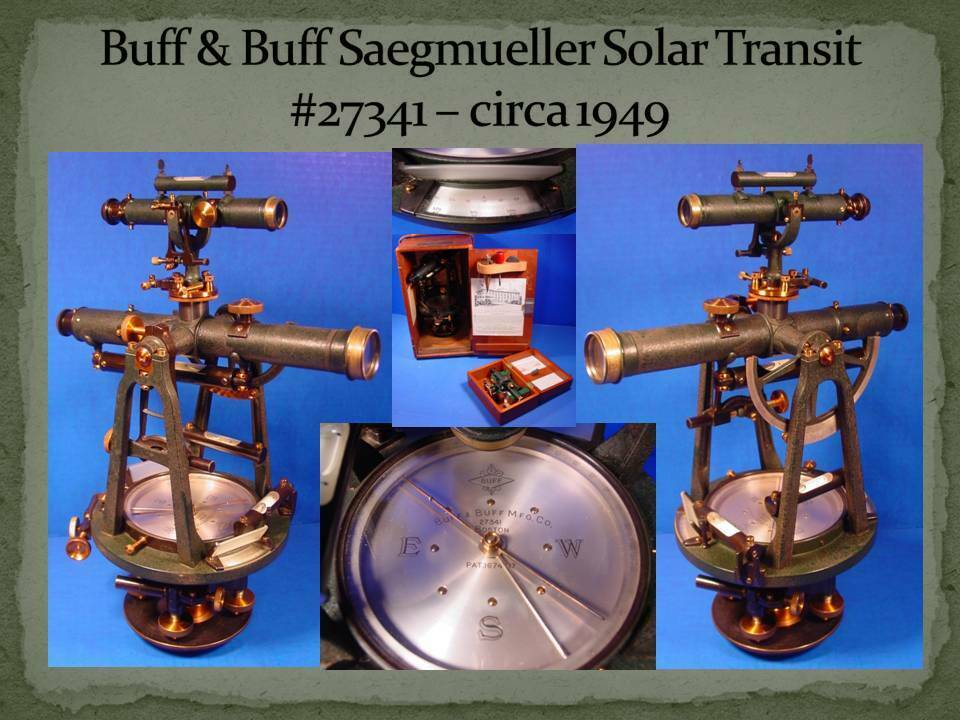

1949 Buff Buff Saegmueller Solar Transit, Exc+ Condition

$ 1452

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

This is one of a pair of beautiful Buff Saegmueller solar transits I am listing on Ebay, the other one dates to 1915. These 2 are likely the best condition Buff Saegmueller solar transits known to exist.

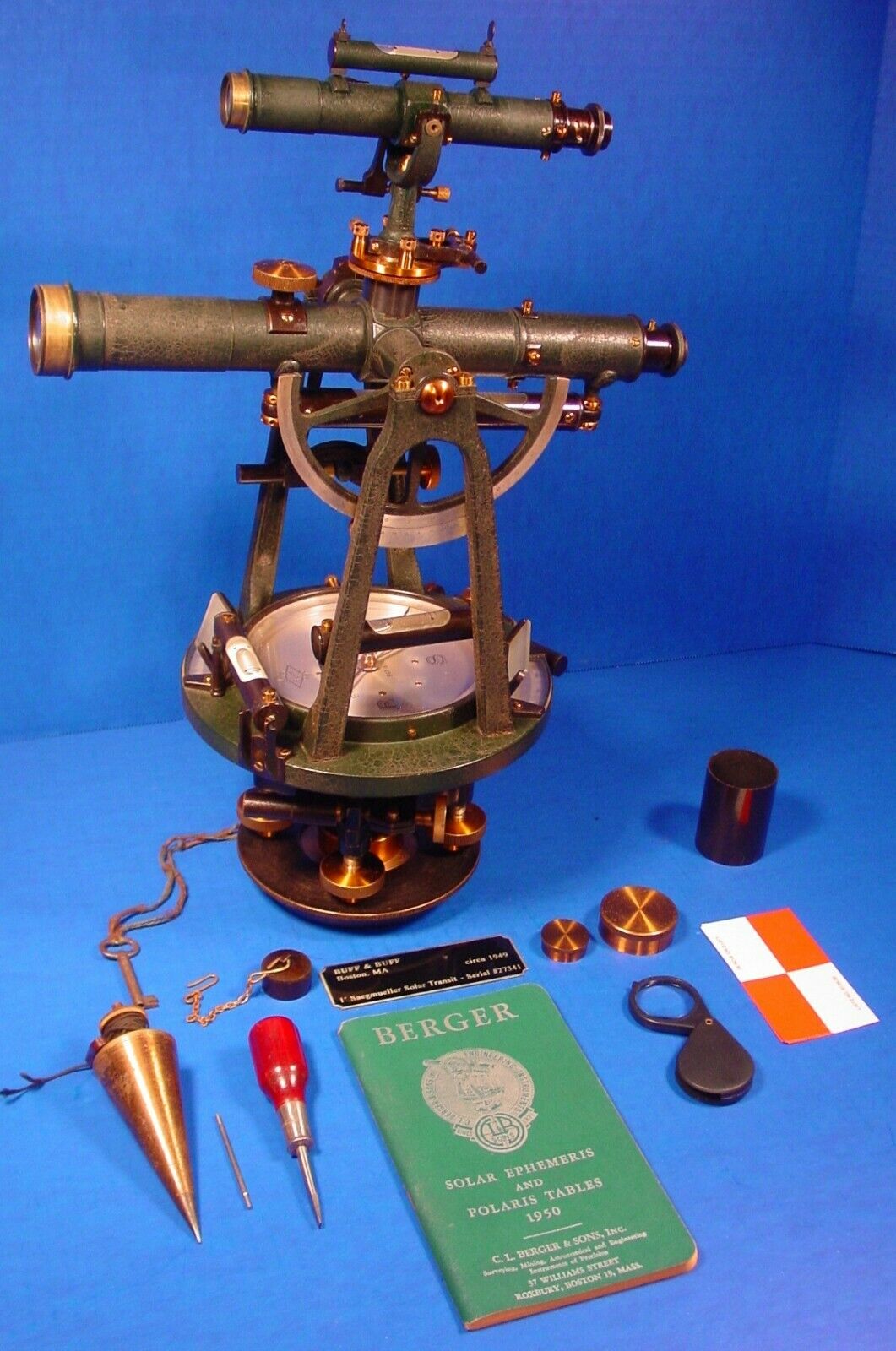

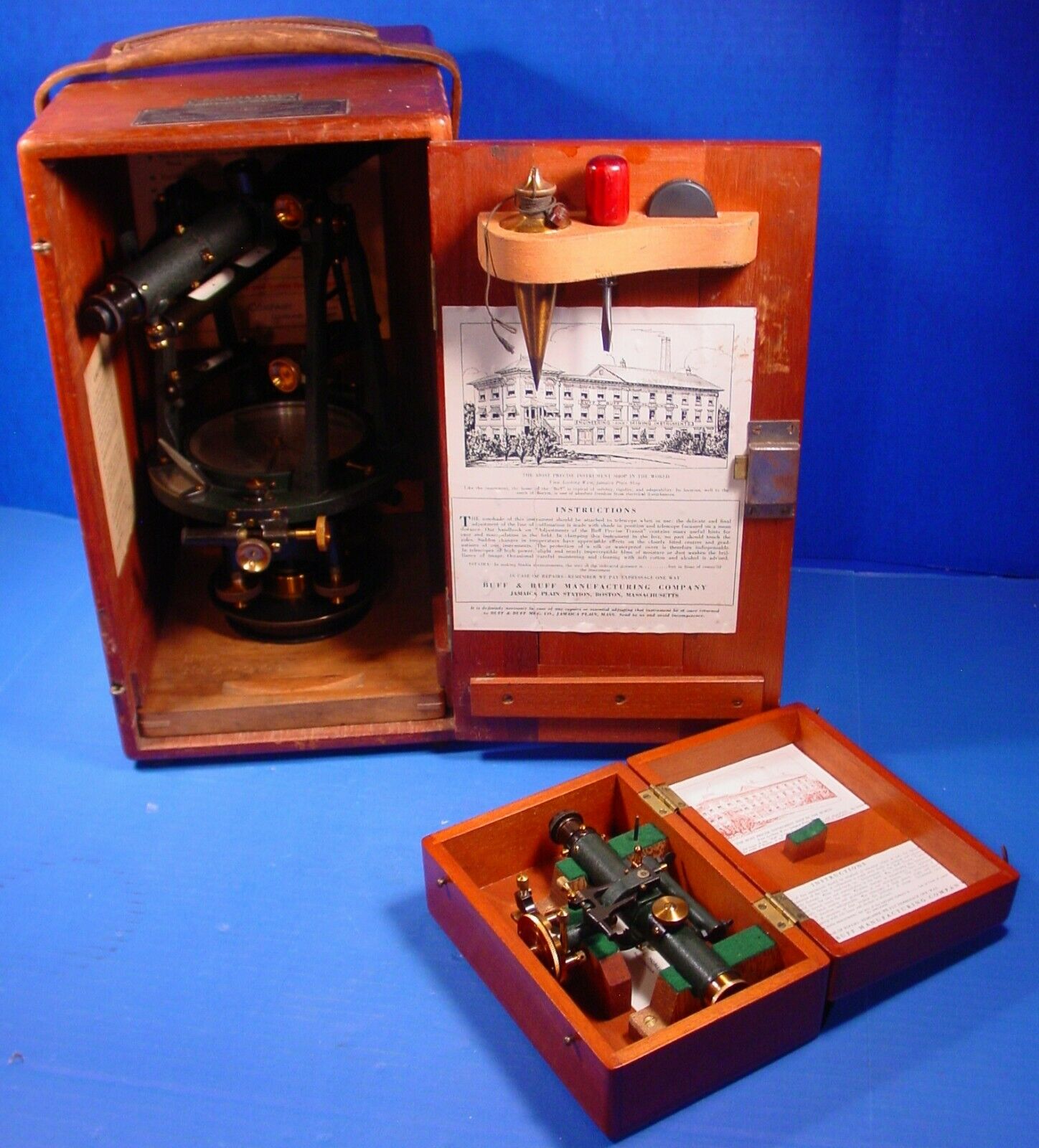

This transit comes with the extras you see in the photos.

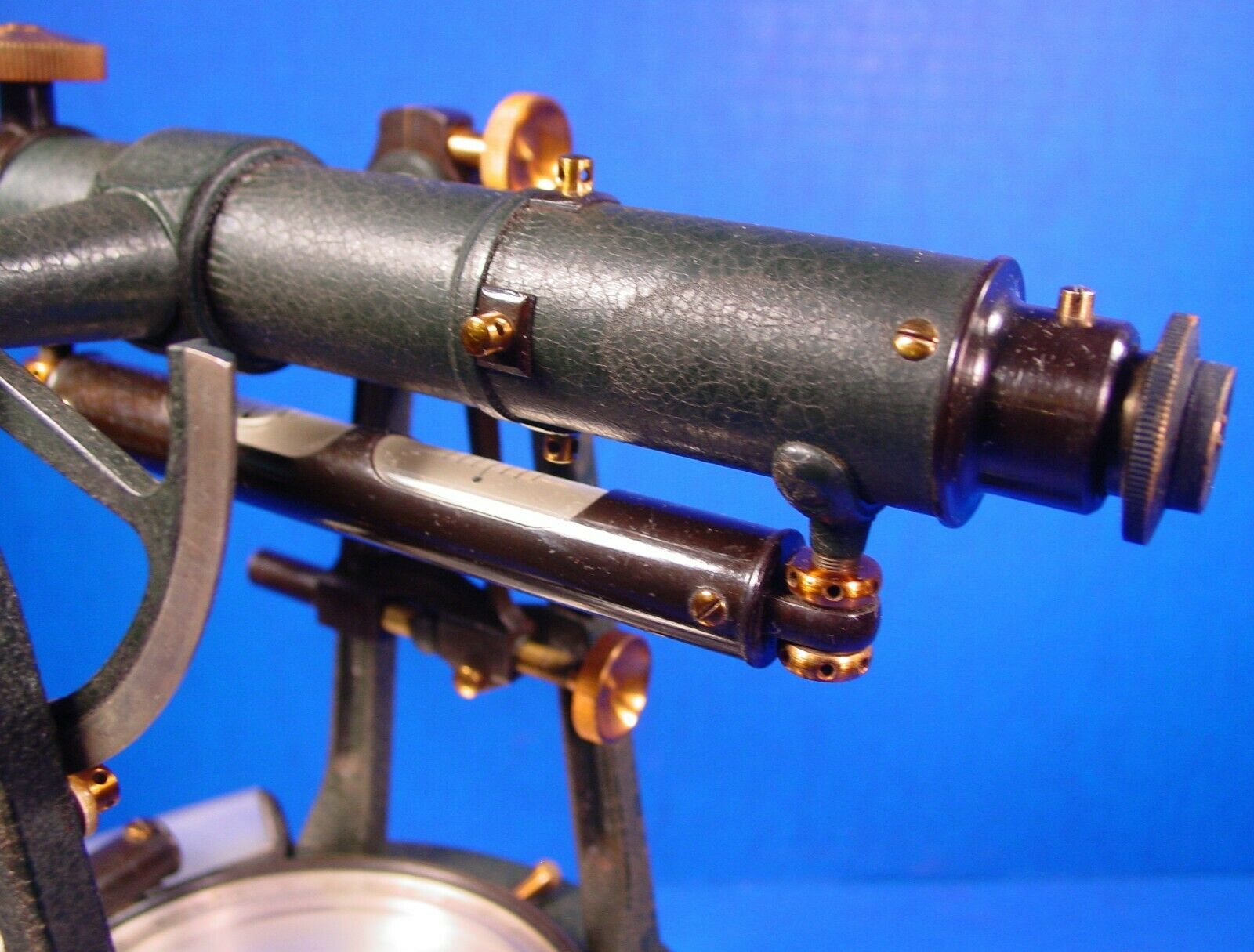

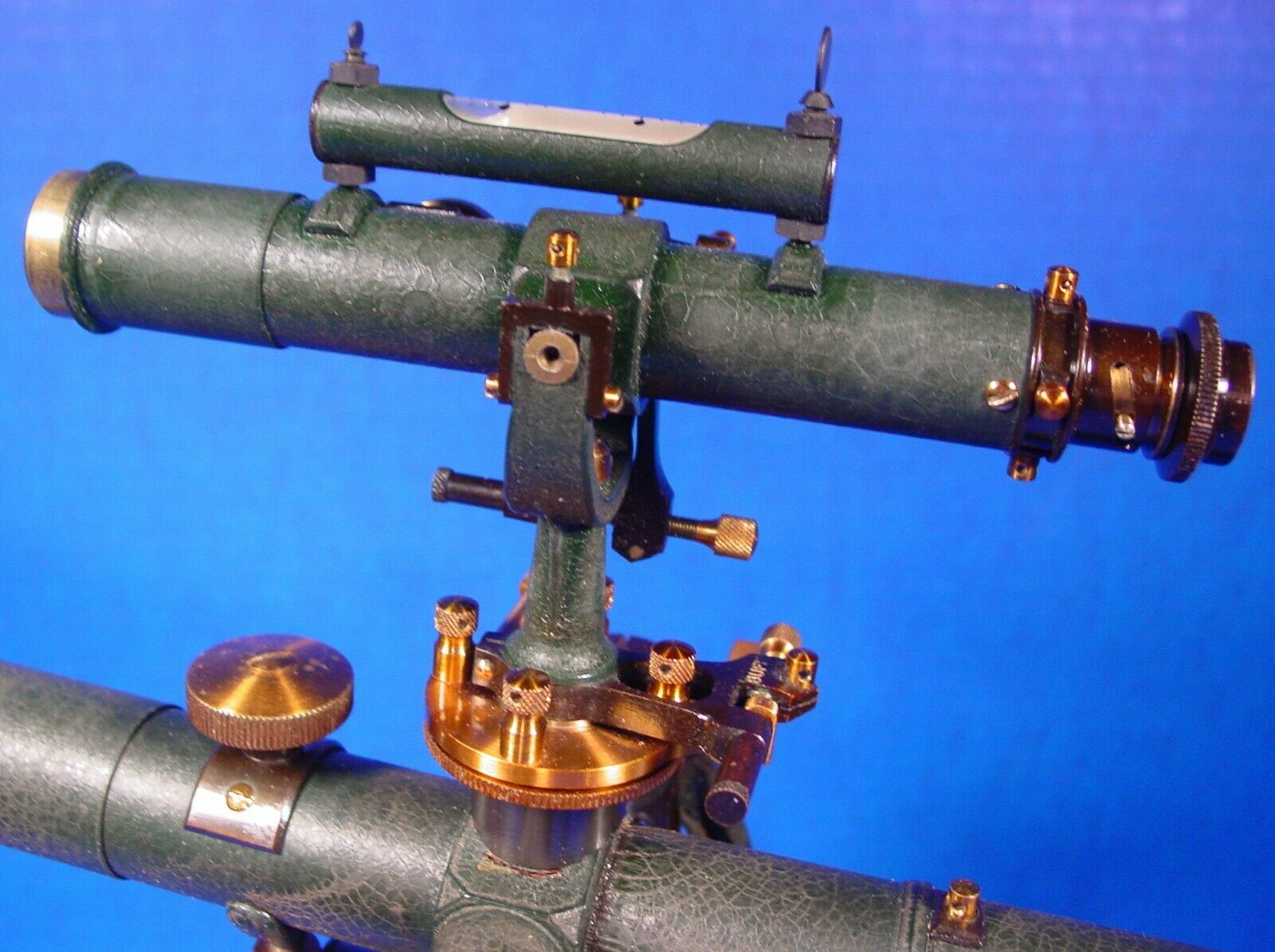

The optics and cross hairs are in great shape, the motions turn smoothly and it comes with the original box.

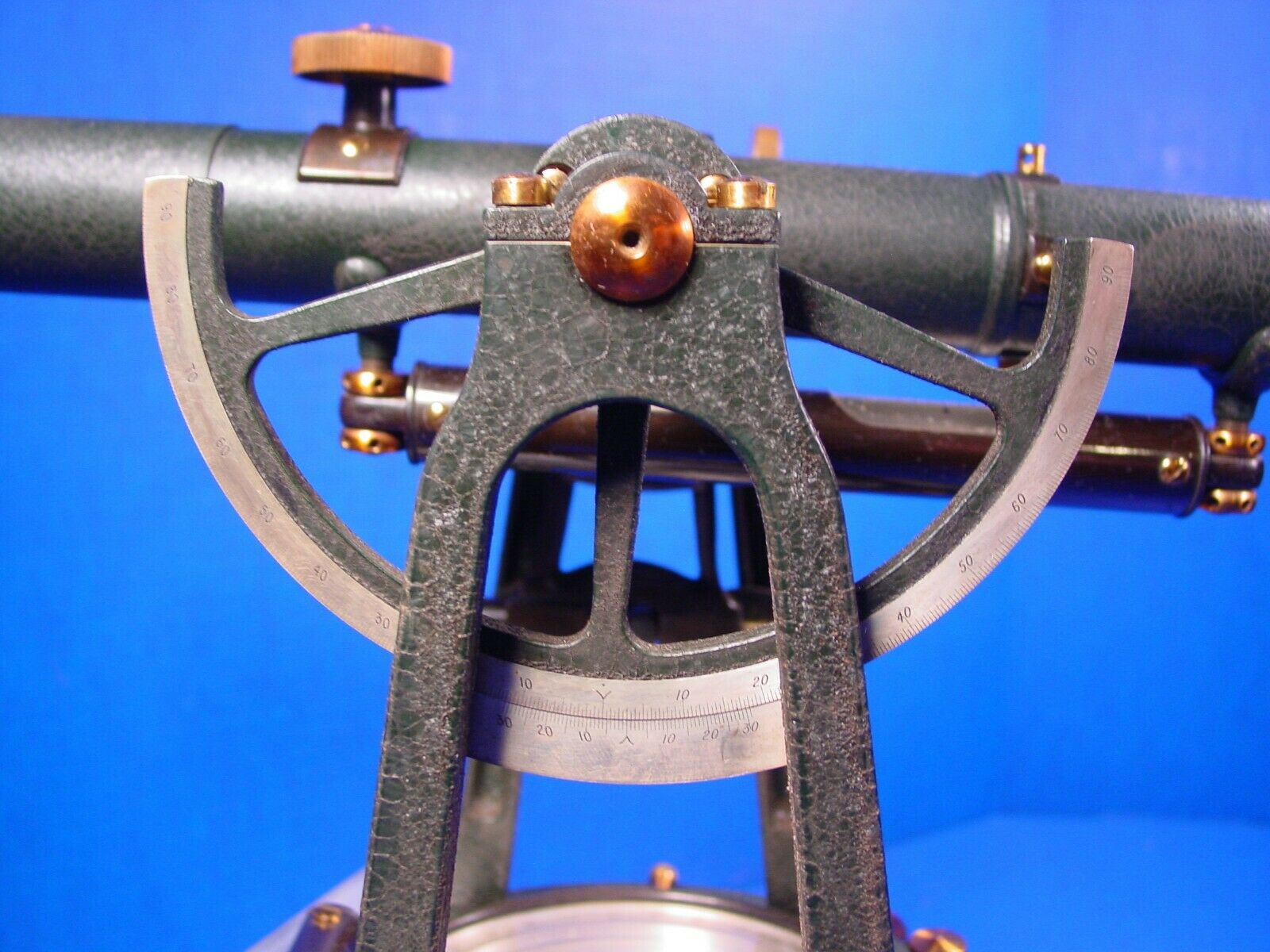

It has an 11 1/2" scope, 6 1/8" Plate, and 4 1/2" needle.

Postage is .00 if within the US, more If you are outside the US; no charge for careful packing.

Here is some information on the firm of Buff and Buff:

Buff & Buff Manufacturing Company

Boston, MA and Green St., Jamaica Plain, MA

1898-1982

(Buff and Berger 1871 - 1898)

(C L Berger & Sons Manufacturing Co. 1898-1962-)

George Louis Buff (1837–1923) was born and educated in Giessen. At age 17, preferring mechanics to the legal career that his parents favored, he went to Hamburg to work for Repsold, a leading German instrument firm. Buff moved to England in 1858 and worked for Thomas Cooke & Sons. He moved to New York in 1864. While working for Stackpole & Brother, Buff came to appreciate the market for the surveyor’s transit and decided to improve the design of this quintessentially American instrument. The result was Buff’s Precise Transit that would remain in production for at least 70 years. In 1869, with the new design in hand, Buff went into business on his own. In 1871 he moved to Boston and, in partnership with Christian Louis Berger, began trading as Buff & Berger.

In 1898, when Buff & Berger closed, Buff went into business with his 3

sons: Louis F. (born 1876; died 1941), Carl W. (born 1879; died 1941), and Henry A. (born 1884).

. Buff & Buff boasted that their new factory, located on the outskirts of Boston at Jamaica Plain, housed "The Most Precise Instrument Shops in the World." At its heart was the dividing engine of 28.5 inches diameter that G. L. Buff built in 1899. Buff & Buff acquired another dividing engine, this one of 48 inches diameter, in 1903. Buff & Buff remained successful throughout the first half of the 20th century, making precise instruments for public and private surveys, but could not adjust to the electronic revolution that swept the instrument enterprise in the post-war period. The firm came to an end in the 1980s.

George L. Buff and Christian Louis Berger went into business in Boston in 1871, trading as Buff & Berger and manufacturing "all kinds of surveying, astronomical, mathematical and philosophical instruments." The new firm was remarkably successful, attracting numerous customers, and winning awards at state and national exhibitions. Buff & Berger boasted two circular dividing engines. The larger, of 3 feet diameter, had been built by John H. Temple of Boston. The firm was dissolved in 1898, and succeeded by Buff & Buff and by C. L. Berger & Sons.

Buff & Buff is a large, long building set back in a courtyard with a steep flight of steps up to a tiny vestibule where there is a Dutch door with a cluttered double office beyond. Beyond the office is a small storage room with low doorways, shelves, cubby-holes, trays, and drawers of instrument parts. Other dark alcoves jut off this room and under the stairs, and other cabinets and parts storage can be seen within.

On a corner shelf in a rickety box is an instrument for testing level bubbles. Transits and surveying instrument telescopes, all dusty, are stowed around. Off this room is another very small room, barely large enough for one man to work. A shelf is built along one wall on which stands an ancient looking instrument with two electrified brass light cylinders on each side and a pivoted magnifying tube in the center rear and a circular clamp in the center. There is a device at the right for holding horizontal over the central clamp a pair of large tweezers, the ends of which are coated with tallow.

Around the shelf and on other shelves packed into the corners of the room are old chewing and pipe tobacco cardboard boxes of the sort that haven't been seen for forty years. The boxes hold eye piece rings to be worked on at the instrument mentioned above. In a covered wooden box below the shelf are racks of wood 2 inches wide by 12 inches long, with a short wooden peg in the center of each short end to allow the racks to be twisted between the fingers of two hands. On these, neatly stacked, with wood strips dividing them like a lumber pile, are spider webs used for the cross hairs applied to the eye piece rings.

Spiders collected once a year from "country" areas around the Charles River or under bridges are put in boxes (one to a box) and taken back to Buff & Buff, where the spiders are allowed to calm down overnight. The next morning the spiders are put on the racks which are then twisted as the spider tends to drop to the floor and thus the webs are wound up on the rack. Good spiders will provide three or four reels each. The web thickness varies from reel to reel, but is fairly uniform on any one reel.

The eye piece rings are carefully scored to show where the cross hairs made from the webs are to be placed. One is carefully aligned on the central circular clamp and the tallow on the tweezers ends is softened. The tweezers are then touched to opposite sides of the rack, which lifts off a length of cobweb. The tweezers are then secured in the right hand clamp and lowered into the correct position so that the web exactly aligns with a set of score marks on the eye piece rings. A few drops of lacquer applied with a toothpick to the ends bonds the web to the metallic part. The web is stronger and more elastic than steel wire of the same diameter.

Behind these two rooms is a long, narrow workshop with four or five parallel tiers of work benches and machining equipment, principally lathes, all powered by a 19th-century system of overhead spindles, pulleys, and leather belts, all humming and thumping together. Only three or four men are at work in this room. One works on aligning two parts of a transit vernier, demonstrating the charcoaling of the vernier scale with a small wooden reverse clamp to hold the divided vernier scale solidly. First, oil is applied to the scale, then a stick of charcoal is rubbed over, and excess oil and charcoal wiped away with a rag.

Other men are turning exact pieces, all individually fitted, although the pieces are received rough from the foundry and successively refined and polished in this room. Trays of parts on the benches and under the benches are everywhere. Some pieces have just been received from the basement where black enamel has been baked onto the surface of various pieces.

Upstairs there is a room where optical lenses are ground. There are cakes of grinding rouge, grinding forms, grinding wheels, and slugs of uncut flint glass. Next, also upstairs, is a repair alcove where instruments sent in for fixing are tended to. On a table is an iron oven where various work is performed (in the old days sometimes lunches were cooked there). There are also two vats of acid to eat off enamel on instruments to be refinished and a coffee pot over a Bunsen burner. More rows of lathes and other instruments, more belts and spindles, more trays of parts and racks of unassembled instruments are found here.

In the basement is a small, locked, double room. It's concrete and musty, containing four dividing engines of various sizes and capabilities, the largest of which is probably in the vicinity of four feet in diameter. These were not in operation while I was there. The rest of the basement is a paint shop and a woodworking shop where instrument boxes are produced.